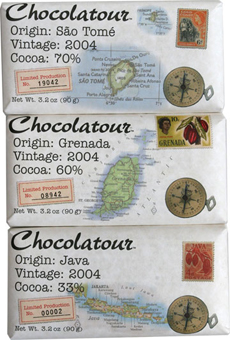

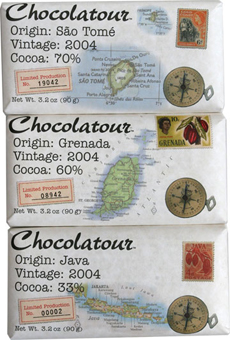

Chocolove’s Chocolatour bars show the country of origin of the beans, the harvest year, and the percentage of cacao of each bar. The reverse side of the package tells more about the chocolate, including the type of bean used (São Tomé is made from a variety of Forastero bean; Grenada from the Trinitario bean; and Java from Java Whites, a variety of Criollo bean.)

|

KAREN HOCHMAN is Editorial Director of THE NIBBLE™. Chocolate 101 was her favorite college course.

|

|

July 2005

Updated September 2006

|

|

Understanding Prestige Chocolate

Single Origin...Semisweet vs. Bittersweet...65% vs. 75%

What Does It All Mean?

What used to be a simple, pleasurable act—buying a chocolate bar—can now be as complicated as selecting a bottle of wine. If you haven’t yet figured out the brave new world of prestige chocolate, as fine chocolate is known in the trade, don’t worry. This is Chocolate 101 in the form of an FAQ. But you don’t get off too easily. There’s plenty of required reading:

The good news is, eating is allowed during class. So surround yourself with your favorite chocolates, and start studying. Just one note about caring for your chocolate:

Chocolate is susceptible to temperature, external odors and flavorings, air and light, moisture, and time. The fat and sugar it contains will absorb surrounding odors. Chocolate should be stored in a cool, dry, odor-free place with good air circulation—but never store chocolate in a refrigerator—it’s too cold and will precipitate bloom. On the other hand, if you have a wine cave, it’s just the right temperature, and humidity too. Many chocolate connoisseurs buy small caves specifically to store their chocolate.

Q. Many fine chocolate bars are now labeled with different percentages of cacao*. What does this mean?

As chocolate connoisseurship has grown, consumers have become more specific in their tastes. Today’s knowledgeable chocolate buyer won’t ask for a “dark” chocolate bar any more than a wine buyer will ask for a “Pinot Noir.” An educated palate will have a preference for specific producers, one or two specific percentages of cacao, and will prefer beans from some growing regions over beans from others.

To get back to your specific question, the percentage of cacao is literally the percentage of cacao in the processed chocolate. This is also referred to as the cacao content. Since a bar is largely made up of cacao and sugar**, the higher the percentage of cacao, the lower the sugar content. (That’s why milk chocolate, which has the lowest percentage of cacao, is so much sweeter than dark chocolate.) The less sugar, the more pure the cacao flavor and intense flavor of chocolate.

- Cacao contents of 30%-49% are classified as milk chocolate

- Cacao contents of 50%-69% are semisweet chocolate

- Cacao contents of 70%-100% are bittersweet chocolate

The latter two groups are both considered “dark” chocolate, but this is a consumer term rather than a trade term.

One hundred percent cacao content bars, which have zero sugar, are delicious to those who enjoy the intense chocolate experience. They are not to be compared to baker’s chocolate, which is also 100% cacao but of a commercial grade. As an analogy, think of a fine wine compared to “cooking wine.”***

*We use the proper industry term cacao instead of the American term cocoa, which was a transposition of letters, probably on a ship’s manifest, in the 1700’s. The word cocoa is properly used to describe the hot drink made of cocoa powder. See the Glossary of Chocolate Terms for a detailed explanation.

**Chocolate is made of cacao, sugar, vanilla, and lecithin. As the latter two ingredients occupy minor percentages, that which is not cacao is largely sugar. Thus, as the cacao percentage increases, the amount of sugar decreases. Milk chocolate also contains milk: the higher the cacao concentration, the less milk and sugar. Lower-grade commercial chocolate can be produced with less than 30% cacao: this is often the product that imparts only the flavor of sugar.

***Products called “cooking wine” should never be used. The alcohol dissipates the during cooking process and all that is left in the food is the flavor of the wine. In the case of cheap cooking wine, this is not quality flavor. Never cook with any wine you wouldn’t drink.

Q. If 70% cacao, e.g., means that 70% of the bar is chocolate, what is the rest?

Generally, 1% or less is vanilla and soy lecithin, an emulsifier; the rest is sugar (a milk chocolate bar has about 20% milk solids). Thus, 29% of a 70% cacao bar would be sugar. However, it is important to note that the percent of cacao includes not only the cocoa beans, but any added cocoa butter. Fine chocolatiers often add more cocoa butter how the chocolate flows and melts; and it provides a smoother mouthfeel.

Q. Are all bars relatively the same, then, given the same percentage of cacao?

No, just as not all 100% Cabernet Sauvignon or Chardonnay wines are the same. The quality of a chocolate, as any manufactured or prepared food product, is determined by both the ingredients and preparation. With chocolate, as with wine, the quality starts with the root stock—i.e., the quality of the tree producing the fruit. While Criollo and Trinitario beans generally produce a finer chocolate than Forastero, there are some superb subspecies of Forastero and there are many hybrids.

- The flavors of the fruit of the cacao tree (the cacao beans are the seeds of the tree’s fruit, a pod) are then impacted by the soil and microclimate, and by the weather during the particular growing season; plus the skill of the farmer tending to the growth and harvest; proper fermentation and drying of the harvested beans. It is at this point that the dried beans are sold to chocolate manufacturers, where they are roasted, ground, mixed with sugar and vanilla (and milk, for milk chocolate), emulsified and conched for smoothness, and then poured into the molds for bars.†

- Each manufacturer has its own “house style” (light or dark roast, amount of conching time, amount of lecithin and vanilla, emulsification or not, addition of extra cocoa butter or not, etc.). So in the hands of different manufacturers, the same beans from the same plantation made into 70% chocolate bars can taste significantly different.

- It is also important to note that, with any other food, quality varies widely. There is high quality and mass quality chocolate, just as there is high quality Chardonnay, coffee, beef, and any product. A chocolate bar labeled 70% speaks only to the cacao content, not to the quality of the beans. The flavor and quality of chocolate are a function of the kinds of beans that are used and the specific steps taken by the manufacturer at each stage in manufacturing process.

- As a case in point, a friend returned from a major chocolate-producing country with a suitcase full of 60% and 75% bars from a local manufacturer. He had purchased for the equivalent of fifty cents apiece—a “steal,” less than the cost of a mass-marketed newsstand candy bar in the U.S. Alas, these “high percentage cacao” bars had a one-dimensional, flat flavor (inferior beans), were a bit grainy (not enough conching time to make the chocolate velvety smooth), had a stringent aftertaste, and were worth basically worth what he had paid.

In sum: Don’t focus on the pure “scores”: 70% isn’t necessarily better than 65%.

- A 70% cacao bar made from mediocre cacao will never be more than mediocre chocolate, while a 65% bar of cacao bar from great beans and a great producer will always be an excellent experience.

- In addition, cacao percentages mean nothing—from a great producer or otherwise—if you don't like the way the cacao tastes at that intensity. If you like semisweet but not bittersweet, you don't want a 70% bar, period.

- Plus, every producer’s 70% (or whatever) bar will taste different from every other producer’s, because their bean blend, roast, emulsification, cocoa butter added and other stylistic elements differ. So you may like Producer A’s 70 percent, but prefer producer B’s 65 percent and producer C’s 75 percent.

†This describes an end-to-end large commercial production. Chocolate is also made into large blocks which are sold to smaller chocolatiers who do not buy and roast their own beans, but buy the couverture from the chocolate manufacturers and melt it (and often blend it, or have the manufacturer custom blend it for them) to make their own bars and enrobed and molded chocolates.

Q. Why don’t labels indicate what kind of bean the chocolate is made from?

While there are many varieties of cacao beans, for reference purposes, they are categorized into three primary tree varieties: Criollo, Forastero and Trinitario (also spelled Trinitarios or Trintario, and a hybrid of the first two). However, cacao trees naturally crossbreed easily; and there are many, many hybrid subspecies or varieties, including those deliberately created on plantations to achieve certain qualities in the cacao. Even the cacao coming from a single plantation or village—such as the highly prized Chuao, from the small village of Chuao in northern Venezuela—is a mixture of both Criollo and Forastero beans.‡ So, while manufacturers keep careful records of each bag of beans they process, given the production process, the blending of beans, and the fact that even single origin beans are not necessarily of one variety, the translation of information to put on a consumer label can get complex, burdensome, and in the end, not meaningful—as with any particular bar (e.g. Brand A’s 75% Bittersweet Bar), the blend will change from lot to lot.

As consumers grow more knowledgeable, more companies will begin labeling their bars by bean type, probably by developing specific lines to showcase the beans. Valrhona was the first to introduce the concept. In the 1980’s, they produced the first vintage year, single origin chocolate bars, where all of the beans (Trinitarios) came from a single domain, the plantation of Gran Couva in Trinidad. They subsequently introduced four other bars in what they call their Grand Cru series, emulating the wine domain designation. Michel Cluizel, Pralus and El Rey also make bars identifiable by origin and bean.

In the United States, Scharffen Berger and Guittard produce single origin bars. The first company to present bars in an educational fashion, promoting not only the percentage of cacao but the origin and harvest year of the bean, is Chocolove. Their limited edition Chocolatour bars (see photo, top left) also include tasting notes on the wrapper.

‡For an explanation of the different bean types, see the Glossary of Chocolate Terms.

Q. So, single origin bars are not necessarily all one type of bean?

Correct. A single origin bar can be one single variety of beans; or it can be a blend (e.g. Criollo and Forastero). “Single origin” simply means that the chocolate was made with beans from one particular area or region; and implicitly, has the flavor characteristics of that region. A bar that is not single origin is called a blended bar, no matter how many different varieties of beans it contains from how many different regions of the world. The correct term for a “regular” bar, one that is not single origin, e.g., is a blended bar.

Q. Are single origin bars better than blended bars?

They are more complex in flavor, and thus of more interest to the expert or aspiring expert. Chocolate connoisseurs will compare single origin bars to the house’s blended bar of the same cacao percentage, as well as to single origin bars from the same origins, made by different producers.

It is important to note that “complex” does not necessarily mean “better.” Many people don’t enjoy complex bars because they want the pleasure of eating a good, basic, undemanding chocolate bar. Single origin bars demand analysis and attention. As an analogy, think of enjoying a glass of young red wine, bursting with ripe fruit, that tells you all about itself at first sip; versus a complex, layered wine that requires you to keep reaching to identify flavors. The first is pure drinking enjoyment, the second is an analytical exercise that provides pleasure to those who enjoy the exercise.

To drill down further:

- The house blended bar is a blend of beans from different locations, even different harvests. By adjusting the blend and other components (amount of sugar, e.g.), the chocolate producer is able to produce a consistent-tasting product from year to year. Whenever you purchase that brand of bar, it tastes much the same: you can rely on what you are getting. (Similarly, non-vintage champagne is blended and vinified to produce a consistent taste each year it is made.)

- Single origin bars will show the characteristics of beans grown in their particular region. For example, Criollo beans from the Sur Del Lago region of Venezuela produce chocolate that is soft and mellow, with sweet spice, soft woods, and sometimes, slight red fruit tones. Criollo beans from Madagascar produce chocolate that is sharper on the palate: vibrant with crisp citrus tartness, often with grape and pineapple-like tones and vodka and white wine notes.

- The notes in the beans can also vary from harvest to harvest, based on growing conditions.

Click here for a discussion of the varying flavors of cacao by region.

Q. Do people really eat 100% cacao bars with no sugar? Isn’t that like eating baking chocolate?

There are more than a few connoisseurs who enjoy eating 99 percent and 100 percent bars. The intimacy of getting that close to great cacao is quite exciting. Try the 100% bar of Plantations Arriba. It is made from the Nacional or arriba bean, which has a higher natural sugar content than other varietals. Thus, even though there’s no sugar in the bar, it has an innate sweetness. You can find it at echocolates.com. Try it plain, with coffee, with cognac or Cabernet Sauvignon, and compare it to their 90% bar. It's the Chateau Latour of chocolate, i.e., it's not for everyone, just for people with very serious palates. But even those who don't crave it should experience it. Other companies make 99% bars. If you see a good manufacturer with a 90%, 99% or 100% bar, try it! But, this is not like supermarket baking chocolate, which is made from the cheapest beans. See the next question.

Q. What’s the difference between baking chocolate I get at the grocery, and baking chocolate or “couverture” from Valrhona or Scharffenberger?

Valrhona and Scharffenberger are two of several top chocolate producers that makes its couverture available to consumers—they tend to be more better-known names because they have good retail distribution. The difference between the baking chocolate on the supermarket shelves and the fine couverture that a top pastry chef would use (e.g., Valrhona and Scharffenberger) is quality of ingredients. It’s analogous to buying a chocolate bar at the newsstand and a chocolate bar at a fine chocolate store—e.g., a Hershey bar or a bar of Valrhona chocolate. There’s a serious difference in texture and flavor when you eat the two bars. The same difference will come out in your baking.

Q. I hear discussions of chocolate that sound like discussions of fine wine. Is this pretentious or legitimate?

In key aspects, chocolate is as complex as wine. If you look at our guide to the flavors and aromas of chocolate, you will find many common descriptors. Also, cacao beans, like grapes, have acidity that is noticeable and important to the structure of the product. And the better chocolate producers are following the path of winemakers to plantation-specific beans that show distinctly different qualities in the chocolate, and are even beginning to indicate harvest years. Here is an analogy:

| |

Chocolate |

Wine |

| Made Of |

Cacao Beans |

Wine Grapes |

| Producer’s Blended Bar |

Blended Bar

The regular “house” bar(s), which can be designated “milk,” “dark,” “semisweet,” etc.; or by any variety of percentages of cacao. Uses a blend of beans. which can come from anywhere.

|

Blended Varietal Wine

The regular “house” bar(s), which can be designated “milk,” “dark,” “semisweet,” etc.; or by any variety of percentages of cacao. Uses a blend of beans. which can come from anywhere. Examples: French Chardonnay (White Burgundy), is a blend of Chardonnay grapes from anywhere in Burgundy.

|

| Origin-Specific Product |

Single Origin Bar

All beans come from the same village or region.

|

Villages (or Village) Wine

Blended from grapes grown in the town, commune, or département where the grapes are grown.* Example: Chablis, a village in Burgundy.

|

| Plot-Specific |

Plantation

All beans come from the same village or region. Example: Valrhona’s Gran Couva bar, where all the beans come from the plantation of Gran Couva in Trinidad.

|

Vineyard

All beans come from the same village or region. Example: Chablis Les Clos. Les Clos is a specific vineyard in the town of Chablis.

|

| Producer |

Chocolatier

Pralus and Chocolove are two different producers (of several) that make single origin bars using beans from the island of São Tomé. Their bars taste distinctly different from each other, because each producer has proprietary recipes.

|

Vintner

Rene Dauvissat is one of nine different producers who own pieces of the Chablis Le Clos vineyard. Joseph Drouhin is another. Each producer’s wine tastes distinctly different from the others, even though the grapes were grown on the same plot of land.

|

*Territorial designations vary by law in each wine-producing country. For simplicity of illustration, we are using the French analogy. U.S. law requires that a wine be made of 80% of both the grape variety and grapes of a particular region to be named, e.g. Cabernet Sauvignon from Napa Valley. Otherwise, it must named, e.g. Red Table Wine from California. Some of the finest U.S. wines are blends, like Bordeaux, to achieve the flavor the winemaker seeks, and thus do not meet the 80% criterion and are blended. Often in this case, the wine is given a trademarked name, like Cain Five or Phelps Insignia.

Q. How should I store chocolate?

Fine chocolate should not be stored in a refrigerator. Chocolate prefers a cool, dry place away from light. The cocoa solids and cocoa butter emulsion remain stable when the chocolate is kept at a consistent temperature between 65°F and 70°F, and at a humidity level between 45% and 55%.

Chocolate is temperamental: it absorbs odors very easily, and it is sensitive to changes in temperature. Moving from cold to warm and back again can cause chocolate to develop a grayish-white “bloom” on the surface. That’s the cocoa butter separating out from the chocolate. It still tastes fine and it’s safe to eat, but it mars the appearance. Find a cool place to store chocolate. The ideal place for both temperature and humidity is a wine cave or refrigerator. Many collectors buy small wine caves to store their bars. Why collect and store bars? To enjoy and compare pieces of different fine bars over time, just as with fine wine!

Plain chocolate bars can be stored for a year or more, wrapped well in foil and kept in the right “wine cave” environment (or a similar cool, non-arid environment).

If you have more chocolate than you’ll be able to consumer in the short term, can freeze it, but it should be well-wrapped and placed in an air-tight container to protect it from humidity and odors. When you are ready to eat it or bake with it, let the chocolate thaw in the container until it reaches room temperature. This will keep it dry and bloom-free.

Q. How long can I store chocolate?

Bar chocolate can be kept for a year or even two, under ideal conditions—wrapped tightly in foil and in the right temperature and humidity. Dark chocolate keeps longer than milk and white: as with fillings and nuts, the milk component will begin to break down while sugar, cacao and cocoa butter have a more indefinite shelf life. The industry is moving to expiration dates but a chocolate will be excellent for at least 6 months beyond and fine to eat indefinitely—when it starts to taste a bit dull, you’ll know (and can turn it into hot chocolate or chocolate chip cookies). If there is no expiration date, ask at the store; and mark the purchase date on the bar if you plan to keep it for a while.

For filled chocolates and truffles from boutique chocolatiers, the best advice is not to buy more than you’ll eat in a week or two. If you’re given a box, don’t hoard it, share it. The finest chocolates are not made with preservatives and should be consumed within two weeks. They’ll still be edible in a month, but the centers will have started to break down and won’t be as flavorful, even if the surface chocolate looks good. Fine artisan chocolates are often made with such complex flavors (Chinese Five Spice, Raspberry Tarragon) that the full nuances start to dissipate after just three or four days. If you are purchasing them directly, ask the chocolatier about the peak eating time: you may want to buy less at a time and come back more often. If you receive chocolates as a gift, you don’t know when the giver purchased them, so the best advice is to start enjoying them at once.

Commercially marketed brands of chocolate like Godiva and Neuhaus contain preservatives and have a shelf life of several months.

More questions? We’re here to help. Click here to ask away.

Chocolate-Lover’s Library

|

|

|

| Chocolate—the Nature of Indulgence: Discover chocolate's role in the history of slavery, war, medicine, and much more. $18.87. Click here for more information or to purchase. |

Chocolate—The Sweet History: This richly illustrated celebration of our favorite indulgence is a beautifully presented history of an age-old delicacy. $26.37. Click here for more information or to purchase. |

Chocolate Desserts by Pierre Herme: Since Herme is probably the best pastry chef in the world, and chocolate the best dessert, it's not a surprise that this book is a dazzler. $25.20. Click here for more information or to purchase. |

Dressed For Success

|

|

|

| Cocoa-Latte Hot Drink Maker: Heats your drinks to perfect temperature every time, and the handy spout makes for easy serving. $27.95. Click here for more information or to purchase. |

Chocolate Shaver: Save your kitchen knives. Easily shave chocolate to make curls and shavings. $8.91. Click here for more information or to purchase. |

Chocolate Tempering: This classic style thermometer is perfect for the temperature sensitive task of tempering chocolate. $9.95. Click here for more information or to purchase. |

Lifestyle Direct, Inc. All rights reserved. Images are the copyright of their individual owners.

|