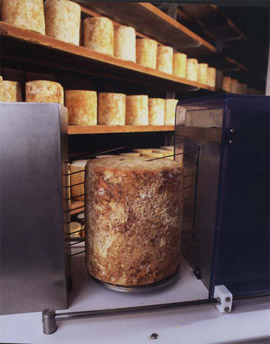

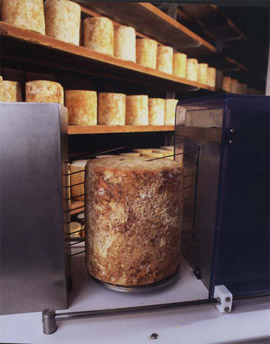

Born in the U.S.A.: Bayley Hazen Blue is made by Andy and Mateo Keehler of Jasper Hill Farm in Vermont, in the style of the classic British Stilton but with its own distinct recipe. The Keehlers learned their craft at Colston-Bassett in Nottinghamshire. Born in the U.S.A.: Bayley Hazen Blue is made by Andy and Mateo Keehler of Jasper Hill Farm in Vermont, in the style of the classic British Stilton but with its own distinct recipe. The Keehlers learned their craft at Colston-Bassett in Nottinghamshire.

|

STEPHANIE ZONIS focuses on good foods and the people who produce them. KAREN HOCHMAN also contributed to this article.

|

|

December 2005

Updated September 2009

|

|

Blue Cheese: In Praise Of The Blues

Page 2: How Blue Cheese Is Made

This is Page 2 of a three-page article. Click on the black links below to visit other pages.

How Blue Cheese Is Made

Blue cheeses, once the closely-guarded secrets of fine cheesemakers in Europe, are now made all over the U.S. Blues are a particularly complex type of cheese to produce. It’s easy for the levels of both salt and mold in a blue cheese to go haywire, and even planned mold growth injected inside a blue cheese causes radical change in the pH of the product, as well as alterations in the fats and proteins.

Also, most blue cheeses are pierced with thin metal skewers, a process often called “punching” or “needling.” Piercing allows oxygen to enter the interior of the cheese, and that oxygen is necessary for proper mold growth. However, it also allows for the potential of unwanted molds and spores. This was best expressed by Tom Johnson, cheesemaker and co-owner of Bingham Hill Cheese Company in Colorado, when he noted that making blue cheese is a process “inherently flawed,” because “you’re taking a perfectly good cheese and poking holes in it, thus opening it up to whatever is in the atmosphere.”

Aging is especially critical for blue cheeses, as well. Most begin the maturing process in a curing room, an area warmer than the aging facility. The relative warmth of the curing room helps to promote mold growth, but if a cheese is left in this environment for too long, it may dehydrate, lose butterfat or have the mold growth run wild—or, alternatively, die out. With all of these variables, it’s easy to understand why blue cheese can be tricky to produce.

Starting The Cheese

Blue cheese production begins, of course, with milk. It can be cow’s milk like Stilton, sheep’s milk like Roquefort or goat’s milk such as Carr Valley’s Billy Blue from Wisconsin. The great Cabrales from Spain is a goat’s and sheep’s milk mix.

- The milk, raw or homogenized, is heated.

- Starter culture, salt, rennet and mold are then added. More about that below.

- Once the curds form, they’re cut and allowed to set. When the curds and whey separate, the whey is drained and the curds are placed into a cheese form.

|

Piercing or punching a Stilton. Photo courtesy of Stilton.com. Piercing or punching a Stilton. Photo courtesy of Stilton.com. |

- After further draining of the whey, the wheels of cheese are removed from their forms and have salt rubbed on their exteriors over the course of a few days (this firms the rind and promotes yet more draining of whey).

- The cheese wheels are then “punched” to allow in that vital oxygen (photo above). The cheeses are ripened further and turned frequently (especially during the early stages of the maturing process) to encourage even mold veining in the cheese wheel.

Is there a most important step or component in the making of a great blue cheese? Come now, did you really expect a single answer to this question, with blue cheeses being made all over the world?

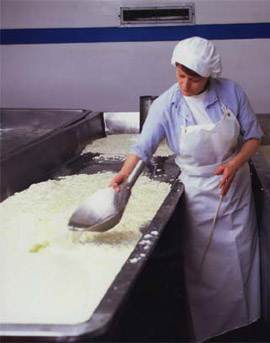

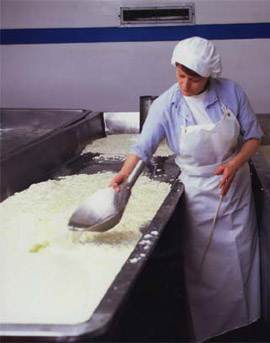

Curd formation. Photo courtesy of Stilton.com.

|

Some producers of blues believe that the key to a great blue lies in using a great milk. Others will tell you it’s all in the curd.

Curd formation is especially important in blue cheese. If the curd knits together in the cheese form too tightly, the interior of the cheese won’t have the proper environment for mold growth. On the other hand, curds that are too loosely knit together in the cheese form won’t provide good passages for sufficient veining and will cause the texture of the cheese to suffer.

Other producers have other opinions.

|

Dawn Morin-Boucher, owner of Green Mountain Blue Cheese, says that the trick to blue cheese is knowing when to pierce the cheese wheel, how many holes to open in it, and when to move the cheese from the curing room to the aging facility.

Almost everyone who produces blue cheese has his or her own theory here, which helps to account for the wide variety of blues produced in the U.S.

Raw Milk Cheeses

There is also an unceasing battle between producers of raw (unpasteurized) milk cheeses and those who begin the process with pasteurized milk. There are cheesemakers who insist that pasteurized milk cheeses can never match the flavor of those made from raw milk, because pasteurization kills beneficial bacteria that add to complexity to the taste. Others assert that pasteurized milk cheeses can be just as flavorful as those produced from raw milk.

The purpose of pasteurization is to kill harmful bacteria in milk; the beneficial ones are killed at the same time. While the incidence of outbreak is infrequent, listeria and salmonella are carried in raw milk.

The argument of the health risks of unpasteurized milk only extends to fresh and lightly-aged cheeses, and while they are sold in Europe and elsewhere in the world, you won’t encounter them in the U.S. The USDA does not allow the import or sale of any raw milk cheeses aged less than 90 days, so that any harmful bacterial in a raw milk cheese will have died before it is sold.

The Molds

How does the mold get into the cheese?

- In the absence of natural caves, which is how blue cheese originated, mold spores are injected into blue cheese to ripen it. Danish Blue is ripened by Penicillium roqueforti, Gorgonzola by Penicillium gorgonzola, Roquefort by Penicillium roqueforti and Stilton by Penicillium glaucum.

- In addition to the blue veins, the molds provide a distinct flavor profile to the cheese, which ranges from fairly mild to assertive and pungent.

- The Penicillium mold will not grow properly until oxygen comes into contact with it, so the cheeses are pierced with pins—the process called “punching” or “needling.” Air is also injected, which causes the cheeses to develop a very high acid content and crumb-like texture.

On the next page, you’ll meet some blue beauties that were born in the U.S.A., made by dedicated artisans.

Continue To Page 3: Great American Blues

Go To The Article Index Above

|